|

| Virgil Ivan Grissom. |

As a small child, I was fortunate to have watched much of the coverage of the Apollo moon landings. During the flight of Apollo 17, I told my mother that my favorite astronaut was Gene Cernan, and I asked her who was her favorite. She became wistful, and without giving me a full explanation as to why, she told me, "Gus Grissom."

I had a National Geographic wall poster depicting all the American astronauts of Project Apollo, grouped by their mission crews, standing on the surface of the moon -- most without space helmets. This was a painting by Pierre Mion, and the point was to be able to see their faces. One group of three astronauts was situated far behind the others. Their faces were effectively blank, which I presume was due to the inability of the artist to paint small features with clear definition. At any rate, to a person viewing this poster at any distance, the faces of those three astronauts would have been indistinguishable.

The poster labeled this crew "Apollo 1".

| Pierre Mion's 1973 National Geographic poster. |

In the days prior to the Information Age, I was limited to library books and occasional Space Program retrospectives on television for information on Gus. It was frustrating as a child, because I felt I should know more about him. I believe I was compelled to pursue the subject of his life and accomplishments in part because I could not get to the bottom of the matter. Most of the books I was able to find merely restated the statistics and technical details of the space missions in which he was involved. We Seven, which was purportedly written by the seven Mercury astronauts themselves (although I suspect really by their Life Magazine reporter friends) was not sufficient to explain some of the mysterious events I had glimpsed in readings or heard about via TV or family.

Those of us who were very young during Apollo weren't immediately introduced to the tragedy which surrounded its first mission. It took some digging to get the answers.

And in that digging, one might also discover that there was another near-tragedy which involved the complete loss of a Mercury spacecraft after it had splashed down. This is not something that was emphasized in elementary school education in the early 1970's. Indeed, there was not much in the public forum that would elucidate on the unlucky Gus Grissom.

In fact, it wasn't until Tom Wolfe's The Right Stuff that the public (at least, those who read the book) had a better understanding of Gus and the odd circumstances of his spaceflight career. And even so, Tom's account may have been based on interviews with another astronaut who was not sympathetic to Gus.

With today's Internet resources, and with the products of my research and travels, I can construct for you a composite image of Gus Grissom in terms of what was important to me: Liberty Bell 7, the Gemini Rogallo Wing experiments, and Apollo 1. Let's take them in series.

Liberty Bell 7

What follows is truly a miracle of the Internet: the complete NBC coverage of Gus Grissom's Mercury-Redstone 4 space mission on July 21, 1961. I implore you to watch it in its entirety, and then I will point out some specifics for you to ponder. Here is the 6-part video series:

First of all, what you just watched is the actual live broadcast as it was seen by the NBC viewing audience - who did not have the ability to record and review it. I enjoyed the apologetic manner of Frank McGee regarding the use of stock footage of blockhouse operations during the countdown because "otherwise we would have nothing to show you".

Also notable is the quality of transmissions from the USS Randolph. The voice of NBC reporter Charles Batcheldor, is very hard to understand, but the technology of the time is on display here -- we should appreciate how far we have come in the world of communications. His transmissions were sent via long wave radio, or "HF" (as opposed to VHF and UHF). HF is notoriously hard on the ears, but it is effective -- if the speaker slows down and enunciates clearly. Obviously this nuance might have helped Frank and company that day.

On my first viewing of this video record, I was absolutely stunned by the way the news of the loss of the Liberty Bell 7 space capsule was revealed. First, I have to fault the NASA announcer, Colonel John "Shorty" Powers, for his lack of tact and awareness. This type of information needs to be conditioned for public consumption - not to hide the facts, but to prepare internal organizations for the onslaught of inquiry. It is okay to take time to prepare for the revelation of bad news, and to contact all pertinent organization leadership to get them ready. Shorty did not do that. Here's a quote of his terse statement on receiving news of the fate of the capsule (48 seconds into part 5 of the video coverage):

I'll repeat what happened downrange at the pickup area. We know that the helicopter attempted the pick-up of the Mercury spacecraft. We know that Virgil "Gus" Grissom got aboard the helicopter. We also know that some kind of malfunction occurred. The spacecraft was dropped in the ocean, and sank.Add to that the reaction shots of people standing nearby the NBC press site, and you get an immediate sense of embarrassment. Now, this is the Cold War, and the U.S. is in competition with the Soviet Union for the high ground of space -- the deflating news of the loss of the capsule put the US Space Program to shame, visibly and instantaneously.

Was that right? Was the emotion of that moment misplaced? Certainly the Space Program had had its share of failures up to that time. Rocket science was not easy. Things tended to blow up. But the way the announcement was made and received indicates a lack of information, at the time, on what was really going on.

Gus Grissom almost died.

Unknown to NASA, NBC, and the viewing public watching the mission of Liberty Bell 7 unfold live, the escape hatch had blown, allowing the capsule to be engulfed and weighted down by water. More seriously, Gus had removed his helmet, and was ejected out of the capsule when the departing hatch sucked the atmosphere from the cabin. His spacesuit filled with water and was dragging him down into the ocean. He couldn't get the attention of the helicopter crew, who were focused on attempting to pull the capsule out of the water. Gus was about to drown.

View the reconstructed story, from the movie The Right Stuff (1983):

Gus did not receive the hero's welcome and parades that accompanied Alan Shepard's triumphant return from space. Nor did he receive deference on his account of MR-4's end: that the hatch "just blew". And there was no way to prove it, because Liberty Bell 7 lay stuck in the muck of the floor of the Caribbean Sea, 15,000 feet underwater. A complete history of the flight, with complete flight-to-ground transmission transcript, can be read here.

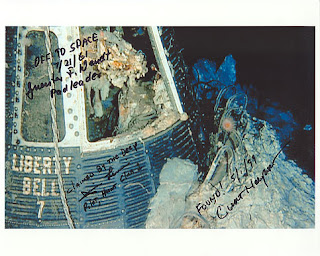

In 1999, after careful planning and robotic exploration of the ocean floor, the location of Liberty Bell 7 was discovered. Moreover, plans were made to bring it back from the watery depths, much to the chagrin of Betty Grissom. And on July 20, 1999, the 30th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing, and almost to the day of the launch of the spacecraft in 1961, Liberty Bell 7 was recovered.

It was hoped that the long unresolved mystery of the blown hatch could be put to rest, through inspection of switch and handle positions inside the cockpit. As it stands, Gus has largely been absolved of initiating action to blow the hatch. However, a true cause may never be found. The hatch itself is believed to be over a mile from the capsule discovery site, and is deemed lost forever:

Because of problems recovering Liberty Bell 7, two days were wasted because of bad navigational data and the recovery vessel kept breaking - Newport had no time to search for the hatch. The answer to the enduring mystery of why the hatch blew may have been in the inside-the-capsule camera that was running when Liberty Bell 7 splashed down. But the camera was found broken open and the film was ruined.Even so, Gus seems to have been vindicated. Something caused to hatch to be blown, but it wasn't Gus. That's not news to Sam Beddingfield, who oversaw the mass properties of all the Liberty Bell 7 components, including the pyrotechnics and explosive bolts used in the hatch:

I was a member of the inquiry team, and we found three or four different ways that the hatch could have blown by itself. Knowing Gus as well as I did, I am certain that if he had blown the hatch manually, he would have told me.

Gus and the Rogallo Wing

After his Mercury mission, Gus was slated to be the first commander of a manned Gemini flight -- Gemini-Titan 3. With co-pilot John Young, who would go into space five times, and walk on the moon, they flew a nominal mission to test out the new two-man spacecraft.

Little known to the public, the designers of the Gemini spacecraft once considered a new mode of recovery. Rather than a parachute landing to a splashdown in water, Gemini might have landed under an inflatable wing and used skids to land on a dry lake bed. The system was known as the Rogallo Wing, after its designer, Frances Rogallo.

Gus Grissom was a significant player in the testing of Rogallo wing concepts for Project Gemini. One wonders if his involvement was a direct consequence of his own travails with Liberty Bell 7. He was one of four active duty astronauts (among several other non-astronaut test pilots) who flew the Parasev evaluation vehicle. Watch how smoothly he pilots the Parasev to a dead-stick landing and rolls up to the camera, taking off his helmet:

Here's an excerpt from the Leon Wegener book One Giant Leap: Neil Armstrong's Stellar American Journey, detailing the Parasev program:

Another innovation Armstrong endorsed was a strange hybrid flying machine called the Parasev - called the "space-age kite", or the "Rogallo wing" after its inventor, NACA engineer Francis Rogallo. Armstrong and fellow X-15 pilot Milt Thompson felt the wing could be stowed in a spacecraft and used to maneuver through the atmosphere. It would give the pilots a large measure of control over their otherwise unpowered craft and would eliminate the need for dangerous, and sometimes sickening, ocean splashdowns. While the idea had little appeal to the NASA Flight Research Center staff, Thompson and Armstrong had considerable clout and were able to get a research version built. Parasev I, as it was known, was an odd looking beast indeed. It was essentially a big tricycle with a single seat. Attached was an angled mast and a thirty-spare-yard parawing. The whole "research plane" cost less than five thousand dollars; it was the first and only craft built totally in-house by the space agency. At first it was towed at sixty miles per hour behind a utility vehicle across the dry lakebed, sending choking clouds of dust into the face of the unfortunate pilot. Parasev's first flights were to an altitude of a few dozen feet, but it worked. Parasev I-A, with a reconfigured stick-and-rudder control system and an improved-design wing, was lifted nearly one thousand feet skyward by a rented Stearman biplane. Armstong, Thompson, and Gus Grissom all flew Parasev I-A, felt they had mastered the device, and wanted to see it deployed. But NASA engineers were still unconvinced and apparently weren't moved by the future astronauts' wishes not to be plunked into the sea at the end of a journey to outer space.

X-15 pilot Bill Dana says NASA used an unfortunate accident as an excuse to scuttle the project. "Neil, Gus and Milt had no problems flying the Parasev. It was a very successful project. But when a guy far less skilled than they were had an accident, they whole project was killed as too dangerous. Neil was disappointed and cursed that it wasn't incorporated into he space program every time astronauts had to be fished out of the ocean at the end of a trip...."Bill Dana's assessment of the cancellation of Parasev may or may not be correct. We do know that a deployment schema was attempted, and the results for Gemini were not encouraging:

The original plan called for the craft to make a landing on solid ground, not water. But the paraglider designs were not going well. Engineers were having great difficulty getting the flexible wing to deploy. It just flat would not! They continued to work on the problem, but NASA finally decided that at least the initial flights would be with parachutes and on water. As it turned out, the deployment problem was never solved in time for the Rogallo wing to be used on any mission. All missions splashed down in the ocean.Gus never did get to pilot his own spacecraft down to a controlled land landing. He probably would have been impressed with the Space Shuttle. He flew the first manned Gemini (capsule named for the unsinkable "Molly Brown") to a conventional ocean splashdown. It is not impossible to imagine him still in the astronaut ranks after the moon missions of Apollo, commanding shuttle missions well into the 1980's, similar to his crewmate John Young.

That was not to be.

Apollo 1

Gus was not happy with progress on the Apollo spacecraft. While he and his crew trained for the first mission of the Apollo program, his frustration was evident. This mission would not go to the moon, instead focusing on a shakedown of the spacecraft systems in preparation for more complex missions that would ultimately perform lunar landings. Unfortunately, his mission would never fly.

Gus died in a ground test of the Apollo 204 capsule, along with Ed White and Roger Chaffee. For those of us too young to remember that event, getting the details took a while. With the passage of time, and the experience of two more lethal disasters involving American astronauts, much perspective and attention has been paid to what became known as Apollo 1.

Here is the entire second episode of Tom Hanks' From the Earth to the Moon, which explores the tragedy of the Apollo 204 fire and its aftermath. Masterfully done, and well worth watching.

In future posts, I will offer additional detail associated with Apollo 1, but suffice it to say, on January 27, 1967, we lost the astronaut who may have become the first man on the moon. In his 1994 biography, the former Mercury astronaut and subsequent chief of the Astronaut Office - and selector of Apollo flight crews - Deke Slayton stated:

"Had Gus been alive, as a Mercury astronaut he would have taken the step." Slayton also wrote, "My first choice would have been Gus, which both Chris Kraft and Bob Gilruth seconded."The topics I have presented here (Liberty Bell 7, the Gemini Rogallo wing, and Apollo 1) are now widely known, understood and available for further research. There are other mysteries of the Space Program that still prove elusive. As we proceed with this blog, I will attempt to uncover some of them for you.

Until then, remember that space is a dangerous business. As Gus himself put it only a month before his death,

"There will be risks, as there are in any experimental program, and sooner or later, inevitably, we're going to run head-on into the law of averages and lose somebody. I hope this never happens, and with NASA's abiding insistence on safety, perhaps it never will, but if it does I hope the American people won't feel it's too high a price to pay for our space program. None of us was ordered into manned spaceflight. We flew with the knowledge that if something really went wrong up there, there wasn't the slightest hope of rescue."Here's a last look at Gus (the astronaut on the right), as he enters the Complex 34 white room prior to the plugs-out test on January 28, 1967. RIP, Gus. And, abandon in place.